DESIGNED TO INSPIRE

CHURCH ARCHITECTS PURSUE A HIGHER CALLING

Friday, July 21, 2005

THE COLUMBUS DISPATCH

For veteran church architect Peter Krajnak, the rewards of his profession are far more than material. They include an enrichment of his faith and the satisfaction of creating a legacy for worshippers yet unborn.

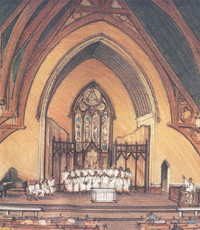

Last month, Krajnak's Downtown firm, Rogers Krajnak Architects, won a nationwide competition to manage the renovation of a historic Washington church where President Lincoln once attended the funeral for a firebrand Civil War general. The Church of the Epiphany, 2 1 /2 blocks from the White House, also was a hospital for Union troops and once counted some of the nation's governing elite as members.

Krajnak, a Roman Catholic, said church work "adds to my spirituality. A lot of individuals within our firm have that same experience; it happens with contractors, as well."

Architect Phillip Markwood feels much the same. He owns a Downtown firm that has worked on about 150 religious projects in the Cincinnati and Columbus areas.

"The most gratifying part of doing work for churches and synagogues is that you get to participate in their ministries," he said. "It's not business as usual. It's providing a service that has a spiritual component."

Religious architecture is intended to create "inspiring spaces," so it's logical that at least some spiritual uplift would attach to those designing and building such works, said David Brems, chairman of the religious architecture committee of the American Institute of Architects.

Some of the inspiration comes from effective use of natural light, Brems said. Selection of durable yet esthetically pleasing construction material is one of the critical decisions in religious design.

As in the secular arena, money often dictates what a congregation can do.

Many of the great cathedrals that have served generations of worshippers aren't possible today because of cost, Brems said.

"We're looking at newer, stronger, yet inspiring materials because we can't afford to build out of handcrafted stone anymore," he said.

Congregations of the past did not expect such features as air conditioning or audio, video and security systems. But these must be included in modern building projects, usually unobtrusively. Parking must be plentiful and easily accessible.

Technology and convenience drive many adaptations, as do changes in religion and society.

For example, Roman Catholic priests celebrated Mass with their backs to the congregation until the Second Vatican Council invited a warmer interaction between clergy and parishioners, Brems said.

Rogers Krajnak's work on Epiphany's renovation plan calls for a balance between the contemporary and historic.

When the Episcopal church was built, its steeple was one of the high points in the area, said Darryl G. Rogers, who merged his business with Krajnak's five years ago. Now, the building is surrounded and dwarfed by 10-story government office buildings.

Since the church organized in 1842, it has made many decisions about what its building should do and be. In the early years, it looked inward, tending to its own spiritual needs.

Now, it is trying to serve more of its neighborhood, offering contemporary and traditional worship, presenting concerts for nonmembers and conducting more extensive outreach ministries, including counseling for mental-health problems and alcohol and drug addiction, as well as emergency food, clothing and housing assistance.

Many of its programs are offered on Sundays, when most other socialservice agencies are closed.

Epiphany's illustrious history includes Lincoln's attendance at the 1862 funeral of Brig. Gen. Frederick W. "Old Grizzly" Lander, a then-famous explorer and poet, who died of a battle wound at age 39.

A century later, Epiphany was grappling with social unrest sparked by the civil-rights movement, not to mention structural damage to the building's foundation that resulted from construction nearby.

The master plan is expected to take about four months to complete; the next phase, fund-raising, should last about two years, said Tripp Jones, chairman of the church's renovation ministry team. No monetary goals have been set, but it won't be a blank check, he said.

"We are not a Cadillac parish by any means," Jones said. "We know we can't fund everything that they come up with, but maybe we'll have to phase things and do a little bit by bit."

One of the things that the church liked about Rogers Krajnak was that "they're working with us; we didn't go to them with a specific list of this, this and this," Jones said.

Before choosing an architect, the renovation team visited some of the places that Rogers Krajnak has designed, including renovations of Trinity Episcopal churches in Toledo and Downtown Columbus, as well as Broad Street Presbyterian.

The team went so far as to set up and tear down the seating when a concert was held at the Toledo church, Jones said. The experience gave the Washingtonians an idea of what it would be like to use flexible seating instead of pews.

If Epiphany tears out its pews, it knows the architectural firm will find ways to reuse the material.

Jones said Rogers Krajnak has a "real gift of taking old things and making them new and making them usable again," such as converting old ends of pews into storage cabinets.

Not all church building projects have such historic considerations.

The McKnight Group, a design and construction company in Grove City, has specialized in building modern churches the past 36 years, said David McKnight, president.

He's not an architect but the group employs 45, he said. Much of their work has been with "fast-growing evangelical churches."

Function, rather than esthetics, is a driving force behind the group's projects, which include Vineyard of Columbus, the First Church of God: City of Refuge and Grove City Church of the Nazarene. Construction is under way for a community center at Vineyard.

"We come at it from a holistic point of view," McKnight said. "We want to make that church better, not just architecturally, but also in strategic planning."

Such planning is intended to ease use of buildings throughout the week and not merely for Sunday worship.

Krajnak said he respects various approaches that houses of worship take in determining how to develop building space, but he chooses projects that balance interests of the past and future.

"It can be very tempting to move a congregation to a new site and build new for less dollars and build specifically for space needed by today's church programs," he said.

Since 1981, he has worked on about 50 religious structures, including a few non-Christian ones, such as Temple Israel, when he worked with another firm.

Fellow architect Andrew Macioce "had great influence on me in understanding the relationship between architecture and liturgy," Krajnak said. How acoustics can enhance or hinder the sung and spoken word is one of the lessons learned, Krajnak said.

Local architect Joe Sullivan of the Sullivan Bruck firm has talked, listened, massaged, arbitrated and done other things in planning several wellknown houses of worship in central Ohio, including St. Brigid of Kildare Roman Catholic Church in Dublin, Worthington Seventh-day Adventist Church and, currently, the sanctuary at First Community Church in Marble Cliff.

"It's a building type that is very important to a community," he said.

Churches run the gamut, and money is always an issue, he said.

"I don't know that I've had one yet where resources meet aspirations," Sullivan said.

Building churches engenders emotional attachment that's lacking in most commercial projects, he said. Members' sense of ownership in their place of worship equals or surpasses the passion they feel for their homes.

Sullivan thinks of a church as a "large family" that must wrestle with a wide range of opinions in reaching consensus on long-term decisions.

His firm has worked on many commercial buildings that have an expected life of about 30 years as well as religious edifices that are "built for generations."

"It becomes a humbling experience when I think of a building that's going to outlive your lifetime," Sullivan said. "You hope it's something that will be valuable to the future."

fhoover@dispatch.com